Discovering the properties of quantum systems that are made of many interacting particles is still a huge challenge. While the underlying mathematical equations have been long known, they are too complex to be solved in practice. Breaking that barrier most probably would lead to a plethora of new findings and applications in physics, chemistry and the material sciences.

Researchers at the Center for Advanced Systems Understanding (CASUS) at Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR) have now taken a major step forward by describing so-called warm dense hydrogen—hydrogen under extreme conditions like high pressures—more precisely than ever before. Their work is published in Physical Review Letters.

The scientists’ approach, based on a method that puts random numbers to use, can for the first time solve the fundamental quantum dynamics of the electrons involved when many hydrogen atoms interact under conditions found, for example, in planet interiors or fusion reactors.

Hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe. It is the fuel that powers the stars including our sun, and it constitutes the interior of planets such as our solar system’s gas giant Jupiter. The most common form of hydrogen in the universe is not the colorless and odorless gas, nor the hydrogen-containing molecules such as water that are well-known on Earth.

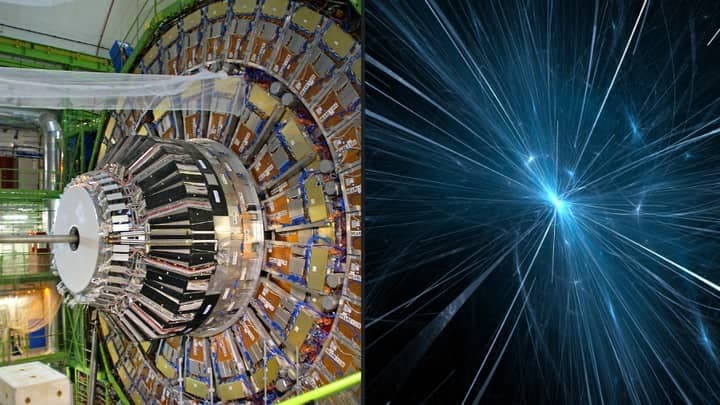

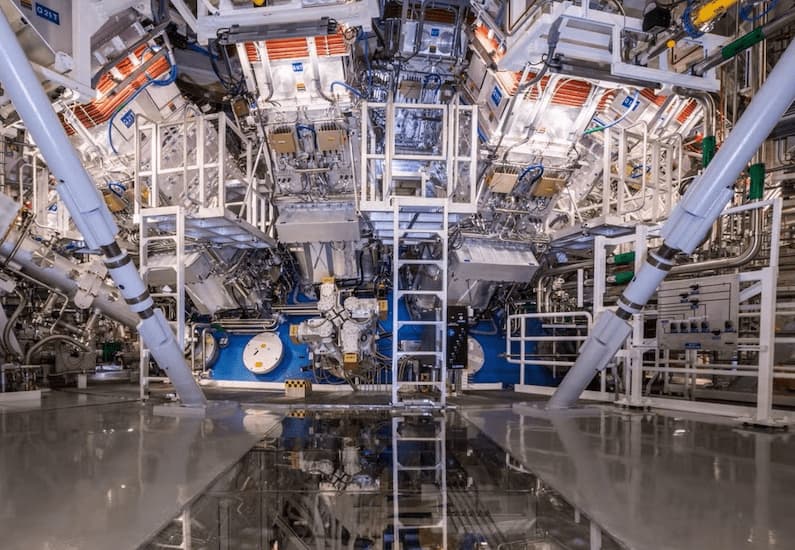

The universe’s stars put down to earth (photomontage): The Helmholtz International Beamline for Extreme Fields is used to create warm dense matter in the lab to study celestial bodies. Now, physicists can make reliable predictions for future experiments.

It is the warm dense hydrogen of stars and planets—extremely compressed hydrogen—that in certain cases conducts electricity like metals do. Warm dense matter research focuses on matter under conditions such as very high temperatures or pressures commonly found everywhere in the universe except for the surface of Earth where they do not occur naturally.

Simulation methods and their limits

Trying to elucidate the characteristics of hydrogen and other matter under extreme conditions, scientists heavily rely on simulations. A widely used one is called density functional theory (DFT). Despite its success, it has fallen short in describing warm dense hydrogen. The main reason is that accurate simulations require precise knowledge of the interaction of electrons in warm dense hydrogen.

But this knowledge is missing, and scientists still have to rely on approximations of this interaction, leading to inaccurate simulation results. Due to this knowledge gap, it is not possible, for example, to simulate the heat-up phase of inertial confinement fusion (ICF) reactions accurately. Removing this roadblock could significantly advance ICF, one of two major branches of fusion energy research, to become a relevant zero-carbon power generation technology in the future.

In the new publication, lead author Maximilian Böhme, Dr. Zhandos Moldabekov, Young Investigator Group Leader Dr. Tobias Dornheim (all CASUS-HZDR), and Dr. Jan Vorberger (Institute of Radiation Physics-HZDR) show for the first time that properties of warm dense hydrogen can be described very precisely with so-called Quantum Monte Carlo (QMC) simulations.

“What we did was to extend a QMC method called path-integral Monte-Carlo (PIMC) to simulate the static electronic density response of warm dense hydrogen,” says Böhme, who is pursuing a doctorate with his work at CASUS. “Our method does not rely on the approximations previous approaches suffered from. It instead directly computes the fundamental quantum dynamics and therefore is very precise. When it comes to scale, however, our approach has its limits as it is computationally intense. Even though [we are] relying on the largest supercomputers, we so far can only handle particle numbers in the double-digit range.”

Higher scales—and still precise

The implications of the new method could be far-ranging: Combining PIMC and DFT cleverly could result in benefits both from the accuracy of the PIMC method and the speed and versatility of the DFT method—the latter one being far less computationally intense.

“So far scientists were poking around in the fog to find reliable approximations for electron correlations in their DFT simulations,” says Dornheim. “Using the PIMC results for very few particles as a reference, they now can tune the settings of their DFT simulations until the DFT results match the PIMC results. With the improved DFT simulations we should be able to yield exact results in systems of hundreds to even thousands of particles.”

Adapting this approach, scientists could significantly enhance DFT, which will result in improved simulations of the behavior of any kind of matter or material. In fundamental research, it will allow predictive simulations that experimental physicists need to compare to their experimental findings from large-scale infrastructures like the European X-Ray Free-Electron Laser Facility (European XFEL) near Hamburg (Germany), the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) at the National Accelerator Laboratory in Menlo Park, or the National Ignition Facility (NIF) at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in Livermore (both U.S.).

With respect to hydrogen, the work of Böhme and his colleagues could potentially contribute to clarifying the details of how warm dense hydrogen becomes metallic hydrogen, a new phase of hydrogen studied intensively both through experiments and simulations. Generating metallic hydrogen experimentally in the lab could enable interesting applications in the future.

- NASA releases 4K video views of the Moon of Apollo 13 ending all conspiracy theories

- A valiant elephant valiantly fends off a group of vicious hyenas, but tragically the calf still loses its tail in an intense struggle for life.

- New Theorem Maps Out the Limits of Quantum Physics

- Unleashing the Power of Compassion: Saving Street Animals in Turkey

- How to know the age of the Sun?